Unexplained activity at a shuttered plant — and the industrial fluoride pipeline still flowing to America’s taps

January 1, 2026

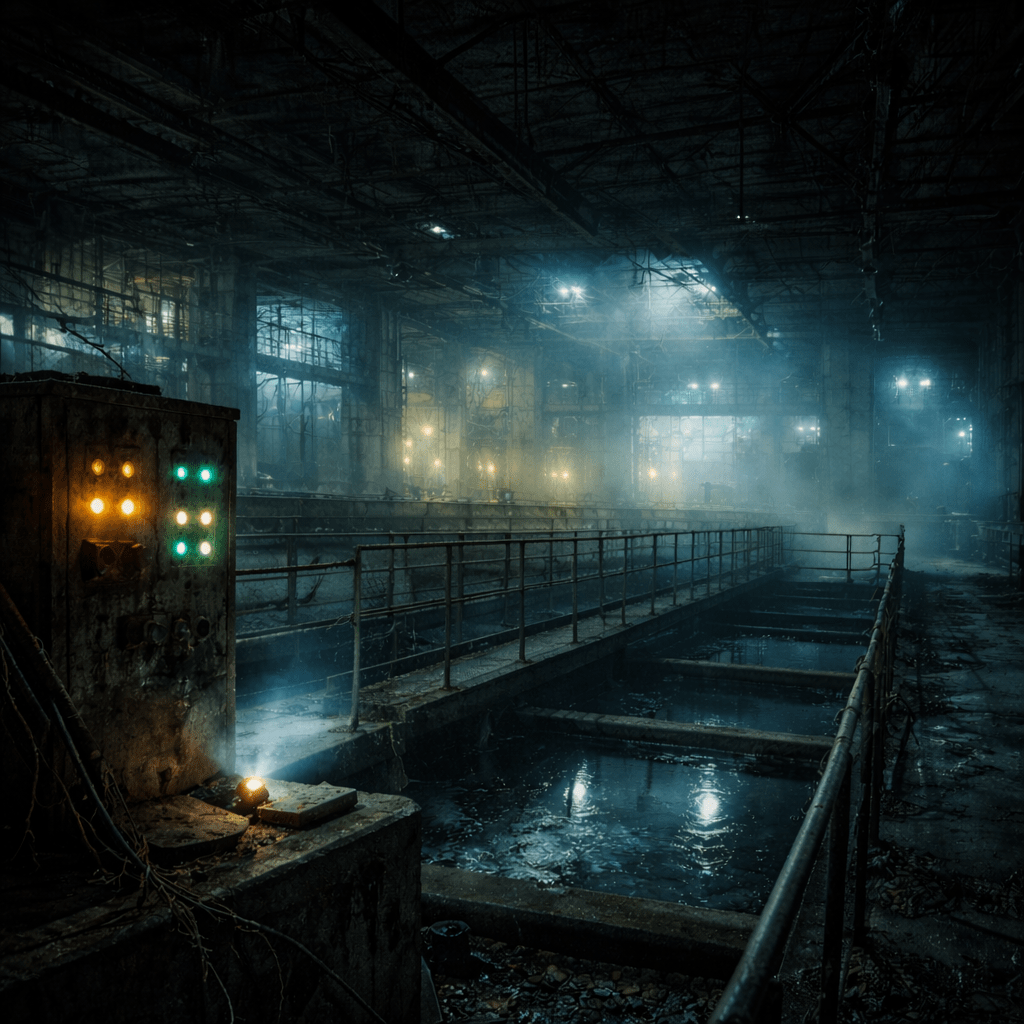

If you drive into Monongah, in Marion County, in the state of West Virginia, at the wrong hour, you might think the town is asleep. Rows of mill houses, the river crawling like an old memory, and that iron smell in the air that you only get in places where industry once boomed and then bled out. But the old Waterworks plant is different. It feels awake.

Locals say the place should be dead — electricity cut, machinery stripped, gates welded shut. But multiple residents report the same thing: lights blinking to life behind cracked windows, the unmistakable whine of motors spooling up, and a pulsing vibration in the ground like something deep beneath the building is breathing. Some nights it’s subtle, like a hum through the pipes. Other nights people say it sounds like the whole water system is trying to come back online.

A former maintenance man, Everett Dales, claims he saw footprints in condensation on the concrete — fresh, heading toward the filtration tanks. “I know what running machinery sounds like,” he said, “and I know what the guts of that building looked like before we gutted it. It shouldn’t be able to make noise. There’s nothing left to spin.” He wouldn’t go inside again, even if someone paid him.

Police reports describe “unidentified figures” on the catwalks. Paranormal investigators describe hearing answers to questions no one asked. The town just calls it the Ghost Flow — the feeling that something in the pipes still thinks it has a job to do.

The Fluoride Supply Chain Nobody Likes Talking About

Far from the haunted brickwork of Monongah, water treatment facilities across America dose drinking water with fluoride. On paper, it’s a public health measure — controlled, measured, dentist-approved. But behind that is a supply chain that reads less like medical care and more like industrial housekeeping.

A significant portion of fluoride additives originate not from pharmaceutical labs or medical suppliers, but from industrial by-products: phosphate fertilizer production, aluminum refining, and smokestack scrubbing systems capturing fluorine compounds before they can be released into the air. Those compounds can be processed, concentrated, and sold to municipalities as hydrofluosilicic acid or sodium fluoride.

To critics, the process looks like a disposal strategy wearing a lab coat. Take what used to be expensive waste, recast it as a “resource,” and let the public utilities become the last step of the supply chain.

The Companies in the Stream

When you trace where fluoridation chemicals come from, certain names float to the surface like driftwood after a storm. Univar Solutions — a major distributor, moving treatment chemicals across the country. Connection Chemical LP — a bulk handler selling fluorosilicic acid directly to municipal systems. Mosaic — tied to the fertilizer sector and the by-products that supply fluoride to buyers. Solvay and Honeywell — industrial chemical firms whose fluoride compounds feed both commercial manufacturing and water treatment.

These companies aren’t doing anything illegal by selling their products. Cities aren’t doing anything illegal by buying them. But legality and comfort aren’t the same thing, and that’s where the argument starts. Supporters say it’s safe at the levels used. Opponents say the issue isn’t the dosage — it’s the origin.

Haunted Infrastructure

Pause and think about that. On one side, a plant the town swears is still running in the dark — phantom machinery, voices echoing through empty tanks, a water purification system that acts like it remembers its job. On the other side, an industrial supply chain that begins at smokestacks and waste streams and ends in kitchen faucets.

Two different hauntings. One supernatural. One bureaucratic.

Monongah’s ghost stories might never be proven. But the pipes? The industrial by-products? The corporate routes? That’s all real enough. And for the people who still live in the shadow of the Waterworks, paranormal activity and chemical distribution feel like two sides of the same coin — the past refusing to stay buried.

The Pipes Remember

A town like this doesn’t need a monster to scare it. It has memory. It has history. It has the echo of industry in its bones. The Ghost Flow isn’t just about spirits in the filtration tanks. It’s about a pipeline that never stopped running — even after everyone swore it did.

Sometimes the scariest part of a haunting isn’t the ghost.

It’s realizing what never truly left.

Leave a comment